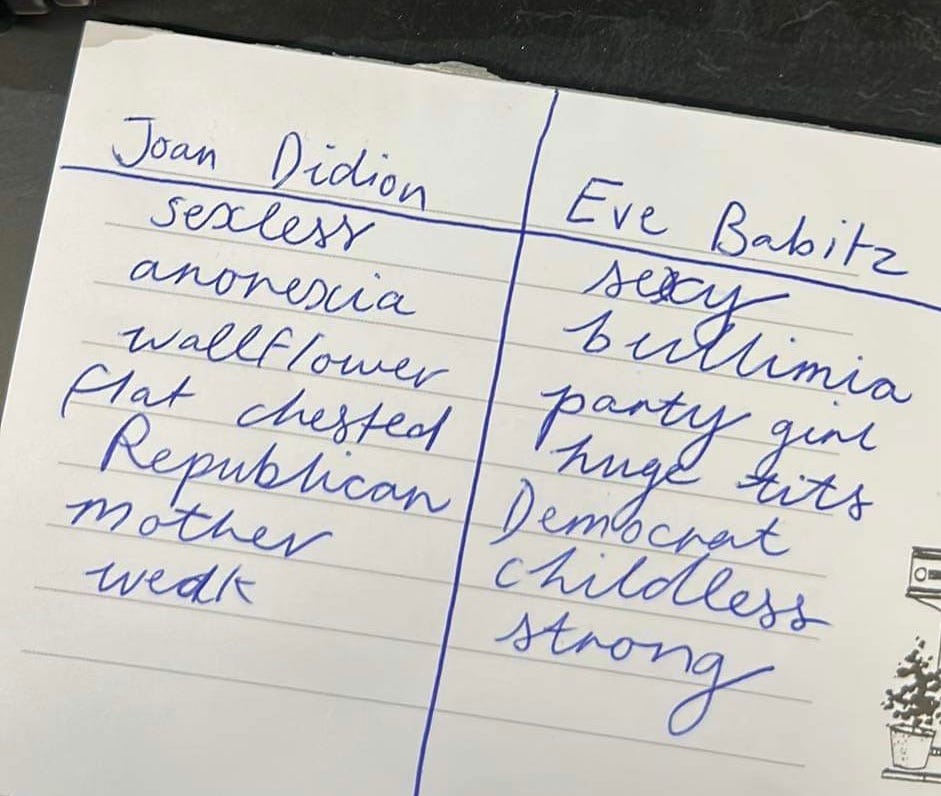

A few years ago, I was standing behind the counter of the quiet store where I worked at the time, on an especially quiet Sunday afternoon. The shop was empty, the necessary tasks complete. I took a pen and drew a vertical line down the centre of a small, lined piece of paper, branded with the name of the store. On one side of the divide, I wrote Joan Didion, on the other Eve Babitz. A series of opposing descriptors of the two mid-century American writers followed. The list was not particularly rigorous, more instinctive and vibe-based. I wrote that Joan was a wallflower, Eve a party girl. Joan was sexless, Eve sexy. Joan was a Republican, Eve a Democrat. Joan was flat-chested, Eve had huge tits. Joan was anorexic (in vibe, and likely in practice), Eve bulimic (in vibe, in practice I’m not sure). However reductive, even cruel, my little list might have been, it pleased me to write it. The list satisfied a distinct itch; it made me feel smug. I showed it to my bookish colleagues. I posted it to my close friends Instagram story.

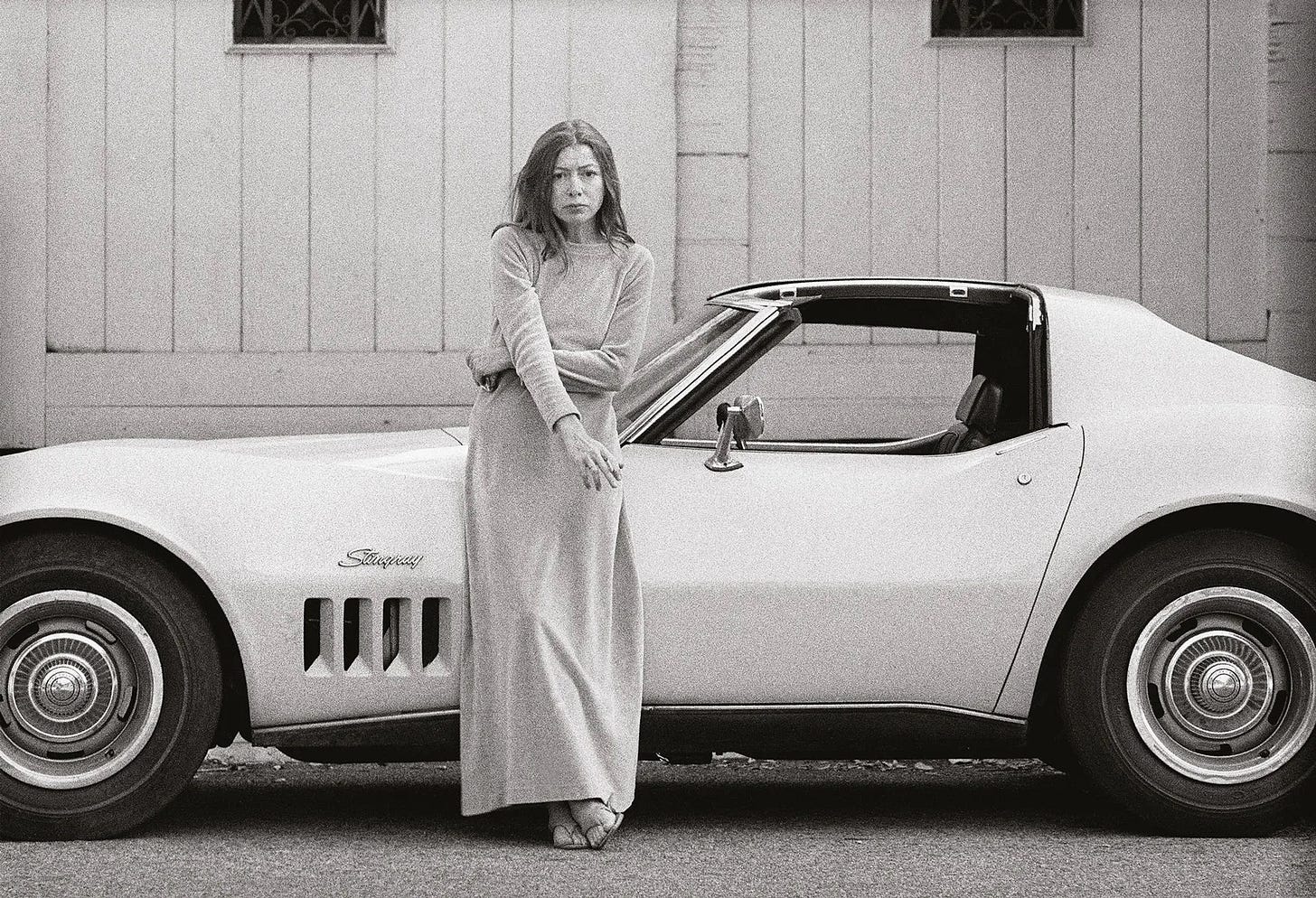

I came to Didion first, at some pimply time in mid-adolescence. I’d like to say it was Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) that introduced me to her. But more likely the introduction came in the form of her endlessly circulated packing list, or the eternal photograph of her in that long silk dress, both of which appeared on my Tumblr dashboard. In the photograph, she stands slightly hunched over, standing against her Corvette Stingray, with one arm crossed over her midsection and the other dangling downward, a cigarette between her fingers. It was the image of Didion that gripped me, before I read any of those lines now imprinted into my mind: ‘We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce’. Or ‘To have that sense of one's intrinsic worth which constitutes self-respect, is potentially to have everything: the ability to discriminate, to love and to remain indifferent’. Or ‘it all comes back.’

Caitlin Flanagan wrote in The Atlantic that ‘women who encountered Joan Didion when they were young received from her a way of being female and being writers that no one else could give them.’ In my shallow and self-conscious teenage years, I received Joan Didion not as a writer but as a mode of living – glamorous living, female living, intellectual living. It was the big sunglasses, the Coca-Colas, the silk dresses, the leotards, the legal pads, the house in Malibu, the cigarettes and bourbon. And the thinness, always the thinness.

I didn’t read Didion properly until my first year of university. An essay from Slouching Towards Bethlehem sat on the reading list of a creative writing class. I think it was On Keeping a Notebook. The memory of first reading the essay – its content and feeling – is fuzzy; the memory of being struck by her sentences is not. Didion’s sentences were perfectly constructed, rhythmic. They were hypnotic and fixating. They were aphoristic and confident, controlled. There was a masculine quality in their drive for authority. In her wonderful essay ‘Dance lessons for writers’, Zadie Smith notes that writers like Didion might inspire devotion because they offer ‘total control (over their form) and no freedom (for the reader).’ Smith writes, ‘every sentence of Didion’s says: obey me!’ Didion’s sentences, like her lifestyle habits, seemed to demand imitation. In the first twitches of what would grow into an intellectual obsession, I read that Didion would retype the short stories of Ernest Hemingway, to understand their rhythm. Inspired, I began copying out Didion’s own essays by hand, mimicking her sentences in my assignments, imitating their syntax and structure. By the time my first year of university had ended, and I had been initiated into adulthood by various humiliations and hurts, I was evangelical about Didion’s essay On Self-Respect. I printed it out in full and pinned it onto my wall.

In the years that followed, I read Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album again and again. During lockdown, most weeks, I would walk for hours (longer than allowed lol), all the way up the Merri Creek to Coburg and back to Fitzroy North, past the urban farms blooming with flowers and sprouting vegetables. On these walks, I listened to Diane Keaton reading Slouching… ‘it all comes back.’ The sentences of both Slouching and The White Album became so familiar that they announced themselves clearly in my mind (often in the sleepy Californian accent of Diane Keaton) whenever they were even loosely relevant to my life. Would I — on a trip to Honolulu a few years ago — have had a drink at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel if Joan had not written ‘I am sitting in a high-ceilinged room in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu watching the long translucent curtains billow in the trade wind and trying to put my life back together.’ Now owned by Marriott, the Royal Hawaiian felt more like the backdrop of an episode of The White Lotus than the site of a literary pilgrimage. I bought a pink rectangular magnet. I walked through the floral gardens and the lobby. And I thought of Joan, sitting fifty years earlier, somewhere above where I stood.

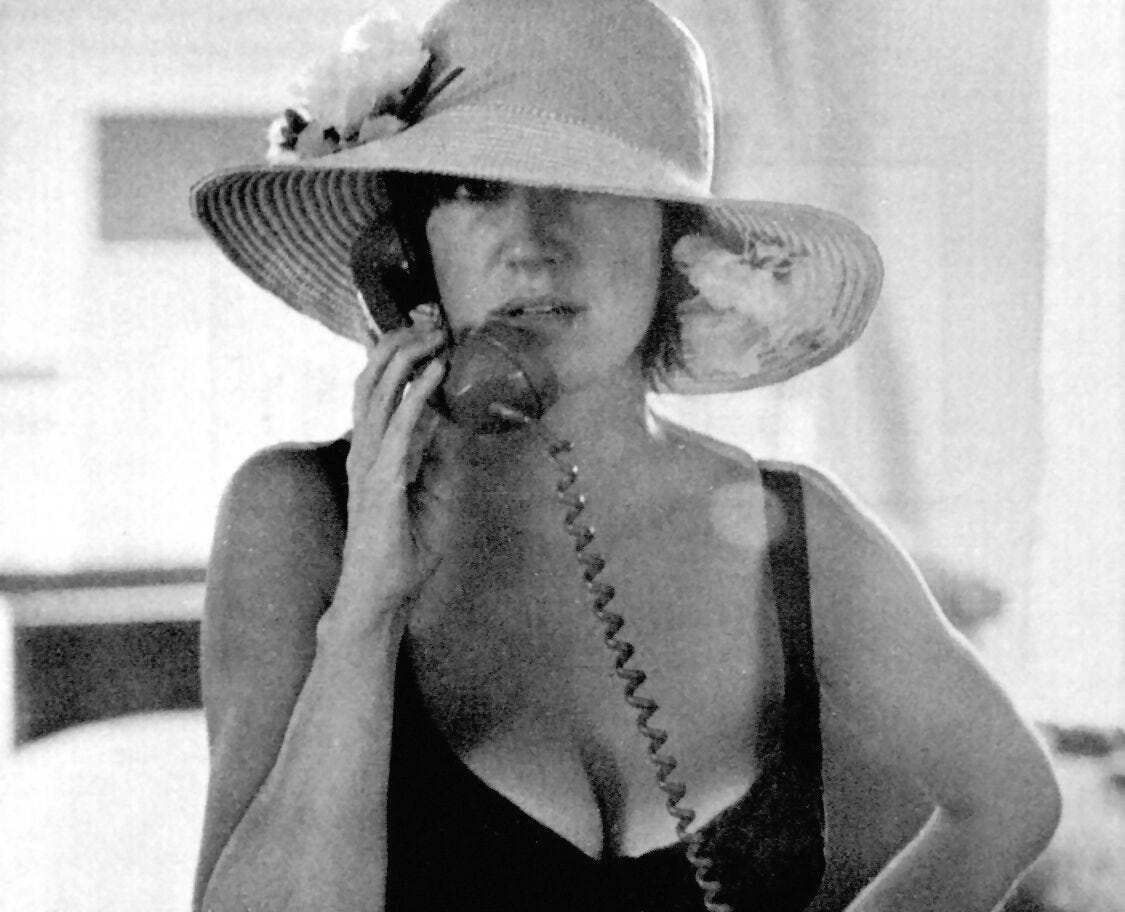

At some point, perhaps at the moment I realised how many other young women shared my affections, as I began to feel like a cliché, I stopped reading Joan Didion regularly. It wasn’t just a self-conscious reflex, I also began to tire of her conservatism, of the tight grip she kept on her readers in her work. Her declarative pronouncements began to feel hollow. It was around this time that I was re-alerted to the existence of Eve Babitz. I think it was about a week before Christmas in 2020, a year before Didion and Babitz passed away within a week of each other. I read Slow days, fast company (1977) late that December, in almost a single sitting, most of it while sitting in a nail salon on the upper levels of a Bourke St Mall, getting an elaborate gel manicure. The book had an intoxicating quality, Babitz’s chutzpah and charisma seemed to be its glue. I loved her commitment to real sensuality, her romanticism. The work seemed frivolous but wasn’t. Like Didion, Babitz was declarative and aphoristic. But her aphorisms always came with a wink, a disavowal of authority. Think, for instance, of the following passage: ‘Women want to be loved like roses. They spend hours perfecting their eyebrows and toes and inventing irresistible curls that fall by accident down the back of their necks from otherwise austere hair-dos. They want their lover to remember the way they held a glass. They want to haunt.’ It's gorgeous, totally delicious prose. Sitting in that nail salon, reading Babitz, I was having a blast. She was so playful, flirting with me. She didn’t want to control her reader. And, perhaps for that reason, no urgent desire to imitate Babitz arose in my reading of her, only pleasure. I would like to return briefly to that Zadie Smith essay ‘Dance lessons for Writers’. Smith uses Muriel Spark, Jane Austen and Joan Didion as examples of writers who inspire devotion and copying. She writes: ‘Compare and contrast, say, Jean Rhys or Octavia Butler, lady writers much loved but rarely copied. There’s too much freedom in them.’ I wonder if Eve Babitz fits into the latter category.

I think, again, of that piece of paper. The question I reach for is: why did I feel the urge, not only to compare these two writers, but to pit them against each other? Why did I feel so smug in reducing these women – both of whom I connect and cling to in differing, compromised ways – to reductive, slightly misogynistic descriptors, like “big tits”. Both writers were Californians, both operated in overlapping scenes in the late 60s – think Chateau Marmont, Laurel Canyon. Both were beautiful and glamorous. Both now receive similarly gross descriptions in their contemporary rediscovery, the worst of them ‘literary It-girl’ (ew). At first glance, they appear conveniently opposite archetypes – Jackie and Marilyn. But I’m not convinced that they are.

Which leads me to Lili Anolik’s recently published, extremely gossipy dual-biography Didion & Babitz (2024). I’m not the first to say that the book is manic and unhinged, full of implausible jumps and frantic projections. Anolik’s sentences are sprawling and tautological, always retracing and correcting themselves. It’s also a fun, engrossing read, a book I would recommend to any Didion or Babitz fanatic, if only for the new archival research and fresh biographical detail. That said, it’s a prickly reading experience for any fan of Didion. From its early chapters, the question Didion & Babitz prompted in me was: why does Lili Anolik hate Joan Didion so much? In the first chapter, she warns us not to ‘be a baby’ about her depiction of Joan Didion. Reading this line, I thought okay….seems intense. But what followed was far more savage than I anticipated. The book blazes with contempt for Joan Didion. Anolik goes to extreme lengths to annihilate her character – coming for her marriage, her ambition and her mothering. In a scathing review of Didion’s Play It As It Lays, Pauline Kael wrote the following of the novel’s protagonist: ‘the ultimate princess fantasy, is to be so glamorously sensitive and beautiful that you have to be taken care of’ (and yeah, frankly, that sounds pretty good to me). Anolik takes the same view of Didion – as a prissy princess. In the world of Didion & Babitz, Didion is at once a princess and a vampire, a writer who will cannibalise anyone for the perfect sentence. In a particularly low blow, Anolik describes the beautiful memoir The Year of Magical Thinking as Didion ‘crawling over the corpse of [her late husband] Dunne, crying all the while, but still crawling, still getting where she had to go.’ Yikes. Anolik wants to have it both ways. Under her warped gaze, Didion is both a ruthless striver who will utilise anyone for her work and an ineffectual little petal who has spawned a generation of “wet blanket” female writers. She seems so invested in and attached to her dislike of Didion that she doesn’t bother to ask why so many of us are so drawn to her in the first place.

The issue is not that Anolik is feigning objectivity. She’s not. She writes openly: ‘I won’t even try to pretend to be a disinterested party here. I’ve picked my side: Eve’s.’ The issue is that, in the book’s insistence on ‘sides’, on tarnishing Joan and venerating Eve, it does a disservice to them both. There is a manipulative flavour to Didion & Babitz. It feels like a set-up – an elaborate construction, an extended straw manning. In the end, the book made me feel slightly ashamed to have ever compared the two writers at all, it revealed the impulse to be an ugly and shallow one. On finishing it, I felt unsatisfied and a little blue, seeing two lives so flattened and bastardised. I walked around my house. I made a cup of tea, did a few rounds of cat-cows, felt restless and vaguely annoyed. I picked up a copy of The Year of Magical Thinking and began to read.

Further reading

Slow Days, Fast Company by Eve Babitz

Hollywood’s Eve by Eve Babitz

Black Swans by Eve Babitz

Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion

The White Album by Joan Didion

Play It As it Lays by Joan Didion

Blue Nights by Joan Didion

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik

Joan Didion: The Centre Will Not Hold (documentary), directed by Griffin Dunne

Joan Didion, Eve Babitz, and the Biographer Who Missed the Point by Laura Kipnis

My Favorite Year: In Los Angeles with Eve Babitz in 1971 by Dan Wakefield

Your Own Private Party by Larissa Pham

The Autumn of Joan Didion by Caitlin Flanagan

Joan Didion’s Magic Trick by Caitlin Flanagan

Dance Lessons for Writers by Zadie Smith

Joan Didion and the Opposite of Magical Thinking by Zadie Smith

Joan Didion and the Voice of America by Hilton Als

Disastrous Surprises by Hilton Als